Needles are inserted to a depth of 4–25 mm and left in place for a period of time (from a few seconds to many minutes). There are often 6–12 needles (and sometimes more) inserted at different acupoints at the same time. The sensation is often described as a tingling or dull ache at the entry point. Many people say they feel very relaxed or sleepy, and some report increased energy levels afterwards.

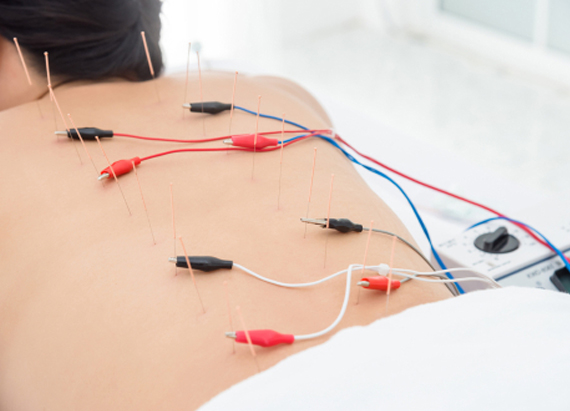

A tiny focused electric current is applied to the skin at the acupoints or can be applied to the needle itself. There are various modalities to consider.

Specific endogenous opiate responses have been reported:

A stimulating heat may be applied onto the needle over the acupoints. Traditionally, this was a smouldering herb.

One to three milliampere is the range used most commonly in clinical practice. This intensity produces a non-painful fasciculation of the muscle in which the needle is embedded. Higher amplitudes cause pain and give rise to a stress response. Stress-induced analgesia depends in part on diffuse noxious inhibitory control and does not usually form a part of acupuncture analgesia.

At least 10 min is required for the production of the endorphins, with maximal release after 20 min. When stimulation is prolonged beyond 1 h, or if the stimulation is repeated (e.g. 30 min bursts repeated after a 1 h interval), the analgesic effect is attenuated.

In laser acupuncture, a fine low-energy laser beam is directed onto the acupoint.

Here, pressure is used to stimulate the acupoints. This can be in the form of a bracelet or strap. This method is commonly used to alleviate motion sickness.

The Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature published by the World Health Organization (WHO) listed about 400 acupuncture points and 20 meridians connecting most of the points. The exact anatomical locations of these points are beyond the scope of this article.

There are 12 meridians on the arms and the legs. Meridians are divided into Yin and Yang groups. The Yin meridians of the arm are: heart, lung, and pericardium. The Yang meridians of the arm are: small intestine, large intestine, and triple warmer. The Yin meridians of the leg are: kidney, spleen, and liver. The Yang meridians of the leg are: stomach, bladder, and gall bladder.

How can unmedicated needles, inserted at sites so distant from their desired application, work? Why does placing a needle on the lower leg, for example, affect gastric function? Many maintain that this is a placebo effect, as these meridians and their Qi cannot be measured, dissected, or observed using standard anatomical or physiological techniques. The acupoints are located at sites that have a high density of neurovascular structures and are generally between or at the edges of muscle groups.

A study demonstrating the map of a meridian pathway, involved the injection of technetium 99 into both true and sham (minimal-depth needle insertion at sites away from traditional acupuncture points) acupoints. The scans demonstrated random diffusion of the tracer around sham points, but rapid progression of the tracer along the meridian at a rate that was inconsistent with either lymphatic/vascular flow or nerve conduction at the true acupoint.1 Another demonstrated that needling a point on the lower leg traditionally associated with the eye, activated the occipital cortex of the brain, as detected by the detected by functional magnetic resonance imaging.

There are several postulated mechanisms of action.

Needling affects the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of the naturally occurring opiate substances: dynorphin (acting at spinal level), endorphin (acting within the brain), and encephalin (acting both in the brain and at a spinal level). Endorphins and enkephalins are potent blockers or modulators of pain arising from the musculoskeletal system. Dynorphin is a powerful modulator of visceral pain; it has a weaker effect on musculoskeletal pain modulation.

The above notions were supported by cross-perfusion experiments in which an acupuncture-induced analgesic effect was transferred from the donor rabbit to the recipient rabbit when the CSF was transferred.>2 The prevention of acupuncture-induced analgesia by naloxone and by antiserum against endorphins offers further support the involvement of endorphins.

Similar to the mechanism of the action of widely used trans-cutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), the neurogate theory has also been offered as an explanation to the blockade of pain. The close correlation between local acupuncture points for pain and trigger points as noted by Melzack3, co-author of the gate theory of pain, represents a major convergence of Western and Eastern knowledge.

The presence of a foreign body (needle) may act to stimulate vascular and immuno-modulatory factors, including those of local inflammation. Adrenocorticotrophic hormone has been shown to be elevated after acupuncture treatments, suggesting that adrenal activation and the release of endogenous corticosteroids may also result.

Acupuncture may induce relaxation of ‘stuck’ myofibrils within tissue planes. This is thought to have a similar effect to the injection of painful trigger points (a common procedure undertaken in pain clinics).

In causing minor trauma to an area of the body, it is postulated that acupuncture may increase local blood flow to the surrounding area. This may initiate or catalyze the healing process.

The mesolimbic pathway is one of the neural pathways the brain that link the ventral tegmentum area in the midbrain to the nucleus accumbens in the limbic system. It is one of the four major pathways where the neurotransmitter dopamine is found and produces a pleasurable feeling when stimulated.

It is postulated that, in chronic-pain patients, the mesolimbic loop is in a state of imbalance. After a relatively brief (30 min) period of stimulation with TENS or EA, a self-sustaining reverberation is set up, causing a re-setting of the pain-modulation pathways. This theory may well account for the long-term analgesic effects seen frequently in clinical practice.